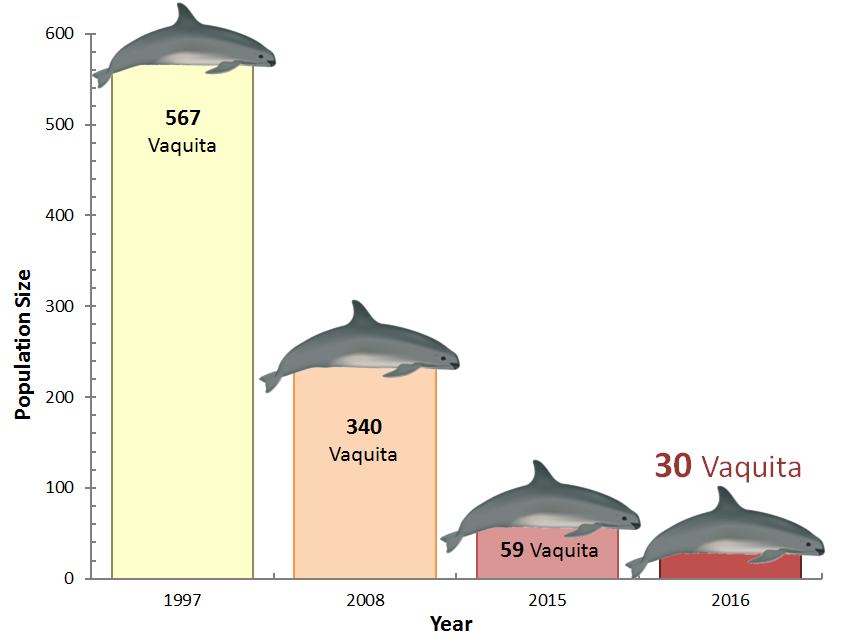

The vaquita is the smallest and most endangered species of cetacean in the world. Its name is Spanish for “little cow” and is also known as the cochito (Spanish for "pig" or "sow"), desert porpoise, vaquita porpoise, Gulf of California harbor porpoise, Gulf of California porpoise, and gulf porpoise. Their numbers have been dropping dramatically, mostly due to getting caught in gillnets used for the illegal fishing of totoaba, a fish that is also critically endangered. Vaquita are easily recognizable by the black markings around their eyes and mouth, the latter of which extends towards the dorsal fin, giving them an appearance of always smiling. Unlike other species of porpoise, they live in warm waters and are generally non-social, except when caring for young (in which case you will see them only with their one calf) or when mating. Occasionally they have been seen in groups of up to 10. Only once has a larger group been sighted, which was about 40 individuals. They are extremely hard to observe in the wild because they spend little time on the water’s surface and avoid boats. They tend to feed in lagoons and are non-selective or opportunistic predators, but they especially like croakers, grunts, and trout, which is what causes them to get caught easily. They are endemic, meaning they are only found in one tiny area of the world, in the Gulf of California between the eastern coast of the Baja Peninsula and the western coast of Mexico. The vaquita has been making waves in the world of zoos and aquaria as the Association of Zoos and Aquariums (AZA) has recently added them to the Saving Animals From Extinction (SAFE) program. Because they are so hard to observe, we for years thought the population was doing better and might survive without human intervention, but recent counts has put the wild population at only ~30 individuals. Unfortunately, it’s estimated that we lose about 30 individuals each year. To try to save the species, the AZA is managing the capture of the remaining individuals and is researching how to care for them and breed them in captivity. Very rarely do zoos take animals from the wild anymore, but exceptions are made when an individual or a species cannot survive there anymore. It is the AZA’s hope that if they can increase the population size and use methods from the AZA’s Species Survival Plan (a breeding program for endangered or threatened species), they can increase genetic diversity amongst the vaquita population so that if they can ever be released back into the wild, they will have the best chance at evolving to keep up with their changing environment and local threats. Learning how to care for these beautiful creatures will be a hard and long process, but if successful, you may see a vaquita in your local AZA zoo or aquarium in the future! AuthorSarah is a conservation educator and trained zookeeper currently working at an AZA (Association of Zoos and Aquariums) accredited zoo in New Jersey while also starting a freelance nature program in Jersey City. Her education specialties include urban environmental programming and access, while her keeping specialties are focused on small mammals, arthropods, and birds of prey.

4 Comments

|

About the blogFerrets and Friends, LLC has four writers bringing you information on a variety of topics from pets to wildlife, education to conservation, and from new developments in our business to information about our industry. Learn something new each week! Archives

August 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed